by M. Elizabeth Osborn (contributed by Grace)

Pericles is one of the most beautiful plays ever written. Its fifth-act

recognition scene, bringing together a Pericles reduced to abject despair

and the daughter he believes dead is among the most moving moments in dramatic

literature. On the stage I have never known it to fail.

In the theatre -- or even rereading it on the subway -- it is the only

scene I know that invariably brings me close to tears.

Writing this is important to me because the standard

judgement of the play is, to put it mildly, rather different; the first

sentence the Arden editor lays on us is: "No one would include Pericles

among

Shakespeare's masterpieces." Now I'm not saying that Pericles

is better than Hamlet or Lear. I am saying that there

are plenty of "masterpieces" -- Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth,

The

Tempest among them -- I've never been able to love as I love this first

of Shakespeare's romances, in which he creates an altogether new kind of

drama.

The story of Pericles, Prince of Tyre, very likely

goes back to the romances of the ancient Greeks; it was widely known for

many hundreds of years. The play was popular in the seventeenth century,

as were other versions of the story in print then. But Shakespeare's

Pericles

is too meandering and too marvelous for the eighteenth century; its brothel

and its incest scenes too offensive for the nineteenth -- and for too much

of the twentieth.

People say that Shakespeare didn't write the whole

thing. This may be true, actually. Anyone who works on the

play quickly sees that scenes (and acts) vary greatly in style, that the

language becomes more and more unmistakably Shakespearean as the play progresses.

The problem is that people say this to put the play down, to dismiss it.

What they don't say is that one mind, Shakespeare's mind, shaped the piece.

Pericles' first adventure is the perfect beginning

for a story that ends in Shakespearean radiance. A young prince comes to

Antioch in search of a bride and finds that the girl is posessed by her

incestuous father, who has her suitors put to death. Many painful

adventures later, Pericles himself, degraded and desolate, has his own

daughter restored to him -- and in the next moment, with heartstopping

unselfishness, gives her to the man who asks for her hand. Today

the moment is interestingly complicated; we are not big on men bestowing

women on other men. Still, what Shakespeare is saying about fathers

and daughters, about human relations is apparent. The symbolic coherence

could not be stronger or, one would think, clearer.

Scholars also like to talk about Pericles

as undramatic. The story is told by the poet Gower, 200 years dead

in Shakespeare's time, and having a narrator is, some imagine, a kind of

failure. Pericles is a good man to whom bad things happen.

He has a melancholy spirit; patience is the virtue he both exhibits and

must learn. All of which makes him an unusual hero, even an unlikely

one. Where is the action? Where is the conflict?

For the first time in 250 years, Pericles has recently

been seen on quite a few stages. Its oddities are what fascinate.

The hegemony of the well-made play, of the fourth wall, of "realistic"

theater, is broken. Storytellers in the theater are now common: A

play that begins with the lines "To sing a song that old was sung,/ From

ashes ancient Gower is come" is still able to cast its spell.

For the first time in 250 years, Pericles has recently

been seen on quite a few stages. Its oddities are what fascinate.

The hegemony of the well-made play, of the fourth wall, of "realistic"

theater, is broken. Storytellers in the theater are now common: A

play that begins with the lines "To sing a song that old was sung,/ From

ashes ancient Gower is come" is still able to cast its spell.

Shakespeare's play calls for pageantry and processionals,

dumbshows and dances. It is filled with music, music with the power to

awake the dead, to recall the near-dead to joyous life. Pericles

actually hears "the music of the spheres"; he tells us this, and we believe

him -- we hear it ourselves.

A play that sprawls all over the place doesn't daunt

postmodern playgoers. Antioch, Tyre, Tarsus, Pentapolis, Ephesus,

Mytilene are names to conjure with. We enter a fabled Mediteranean

world -- or more accurately, a series of worlds, each radically different

from what precedes, and what is to come. We are greeted with low -- and

dark -- comedy, and we witness miracles: A woman is raised from the

dead, a long-lost wife and a long-lost daughter are found, a god speaks

to man. This "undramatic" play is in fact theatrical as hell.

I fell in love with Pericles when I saw it

in the early 70's, at Canada's Stratford festival. The moment I remember

best came early, in the second act, when Pericles is at Pentapolis, on

the happiest night of his life. A shipwrecked vagabond who has nonetheless

managed to outdo all other knights an feats of arms, he is being honored

at a great feast, waited on by the beautiful and eager king's daughter

who will become his wife. But in the midst of the festivity Pericles, characteristically,

is subdued. He looks at the good king Simonides and thinks of his

dead father, sees the splendor that surrounds him as ephemeral. At

Stratford the merrymaking came to a stop, and Nicholas Pennell turned out

to the audience and told us what Pericles has just understood: "Now I see

that Time's the king of men; / He's both their parent, and he is their

grave, / And gives them what he will, not what they crave." Then Pericles

took this deeply felt and melancholy vision of the nature of mortal life

and turned back to the world of Simonides's court, embraced the love of

Thaisa. The revelation shaded everything to come.

In his 1987 Hartford Stage production, Mark Lamos

began with a little girl reading a book, thereby summoning up Gower, who

summons up the story. More than once I had seen a boy used in this

way, in a production of Shakespeare, but never a girl. The sight

warmed me. Looming above and behind the action was the head of a

woman; it might have broken off a gigantic Greek statue. The creation of

designer John Conklin, the image suggested Diana, the god of this play;

it represented the Other that Pericles seeks, and finds at last. I've never

seen the play's spiritual dimension so powerfully present.

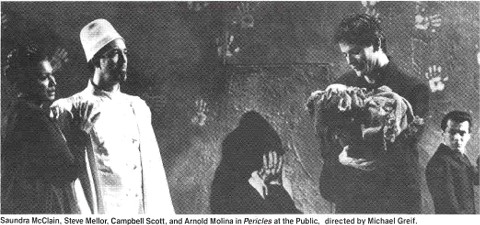

The final dress rehearsal of Michael Greif's Pericles

at the Public, five days after Joe Papp's death, was inevitably an emotional

event. In the theater's weekly handout, Greif says that "Pericles

is about how we cope, individually and collectively, with the loss of people

we love." It truly is a play filled with grief: It is touching to

watch Campbell Scott live through the role of Pericles so soon after the

death of his mother, Colleen Dewhurst; touching to think of Greif struggling

to get this enormous play under control while simultaneously dealing with

the loss of a beloved father figure. Pericles is the perfect play

for the Public to be doing just now.